It is difficult to know just how far to trust illustrators. Take a look at the accompanying picture from “Worrals Down Under” of the three girls standing in front of the lonely shack in the outback of Wallabulla and see whether you think Heade got it right. It really is such a contrast to the distant views we normally get of Worrals and Frecks in their flying kit that it is worth a closer look. You can actually see details of the faces and you can certainly trace the suggestions of their figures.

The caption says,

“This place ain’t fit for girls,” he stated emphatically.

Somehow “girls” doesn’t seem quite the right word to describe the females represented in the illustration. These are attractive young women in the prime of their sexual potency. It is inevitable that they should attract the attentions of young men. In one way, certainly, Heade’s picture is definitely imp robable for, amidst the dust and heat and primitive conditions of an Australian desert station, they appear remarkably well-groomed and totally inappropriately dressed. Lipstick is in place, hair-styles are under control and, from what we can glimpse of the footwear, there seems to be a suggestion of a high heel. No doubt about it they are glamorous. Worrals, Frecks and Janet but do you know which is which ? Let’s have a look at W.E. Johns’ descriptions and see if definite identifications can be made.

robable for, amidst the dust and heat and primitive conditions of an Australian desert station, they appear remarkably well-groomed and totally inappropriately dressed. Lipstick is in place, hair-styles are under control and, from what we can glimpse of the footwear, there seems to be a suggestion of a high heel. No doubt about it they are glamorous. Worrals, Frecks and Janet but do you know which is which ? Let’s have a look at W.E. Johns’ descriptions and see if definite identifications can be made.

You already know that it’s got to be Worrals at the front. Her assertiveness and defiance is implicit in her body posture. On her own Frecks can deal boldly with the many adversaries that the girls confront but when Worrals is there she always fades into the background. Worrals is the leader and she is the one “seeing off” the villain in this picture. However, let us look at the author’s own words when he first introduces her in “Worrals of the WAAF”.

Not even her friends could truthfully call Worrals pretty, although her features were regular enough perhaps too regular: but that she was attractive in a way not easy to define no one could deny.

This is still rather vague and generalised. There will always be a range of opinion about what is considered to be “pretty”. In his next sentence W.E.Johns becomes more specific.

She was dark; her hair was brown and always tidy; her eyes, the same colour, were steady and thoughtful except when softened by a flash of humour as they often were. They could also gleam aggressively when things went wrong.

Take another look at the illustration. Heade has got it right about the hair. We can’t see the details about the eyes but once again the position of the arms and the stiffness of the body with the sideways stance and the left shoulder presented forwards to the bearded rogue suggest the latent aggression.

Her nose was well cut, with delicately chiselled nostrils, and balanced a firm mouth with lips that were, perhaps, judging by orthodox standards of beauty, a trifle too thin.

Yes, there is a sharpness in that face, perhaps enhanced on this occasion because her eyes are narrowed to face the setting sun and appear as no more than slits below pencil-line thin eye-brows and a firmly closed mouth.

Of average height, her figure was slim and neat continues Johns. Though her waist does not appear as waspish as the girl in the yellow dress, there are no contradictions here. Because Heade has placed her centre stage and above the level of the men it is difficult to determine her height. She dominates the picture and this agrees well with the next suggestion of the author,

She carried herself with a quiet air of authority that seemed to come natural to her…

That’s the easy part over for, whilst no one could mistake Worrals, deciding which blonde is Janet and which is Frecks is a lot more difficult. It wouldn’t matter how many times we enlarged the picture and studied the faces we still couldn’t get close enough to see the brown blotches that give her the name from her freckles.

Betty’s mirror having told her that she had no pretensions to good looks, she wasted no time in trying to devise by artificial means what nature had denied her.

This is the rather cruel way in which she is introduced in “Worrals of the WAAF”.

Her straight flaxen hair was usually out of control, and her blue eyes laughed at those who advised lemon juice for the freckles which appeared every summer on each side of her small aggressive nose, to pro vide her with a nickname which she accepted philosophically, as she accepted everything else that came along.

vide her with a nickname which she accepted philosophically, as she accepted everything else that came along.

Heade can’t show you the blue eyes and it is difficult to judge whether either of the girls depicted has “straight” hair. On balance the girl in the yellow dress seems the more likely especially when we consider that Johns tells us that Frecks had a “slight wiry figure”. Study yourself the picture from the front of “Worrals in the Wastelands” and compare it with the “Down Under” picture and see if you think Stead has been consistent in his depiction of Worrals’ “side-kick”.

The girl in the blue dress does look slightly more doll-like which would suit the more passive role played by Janet in the story. On the other hand Janet is known to have courage and resolution for she won the George Cross for bravery during an air-raid. No - it is impossible to come to a final conclusion. What matters is that, by most standards, all three girls, as depicted by Heade, would seem to have physical features that make them look attractive.

This discussion about the author’s intentions and the illustrator’s ability to fulfil them is not just a peripheral matter or a mere question of aesthetics. I hope to show that it goes to the heart of the problem that WE Johns set himself when he created Worrals.

The story has often been told about how the books were written as a form of recruiting propaganda in order to get girls to join the WAAF. It seems certain that it was successful for the “Gimlet” team were then put on parade to do a similar job for the army. Unlike Biggles who evolved and went on evolving from World War One onwards, Worrals had to spring to life instantly and be the essence of what all girls required from a heroine. Facts certainly did not matter to W.E. Johns. The central idea of the early Worrals stories is actually based on a fallacy. Girls in the WAAF did not fly aeroplanes, ferry pilots belonged to the ATA. For further details of this whole war-time phenomenon you cannot do better than look at “Women with Wings” by Mary Cadogan. In that book she suggests that girls “inspire d by Worrals to join the WAAF” found life there rather tame after the gloss of the heroine’s flying exploits”. Interestingly she also adds, “It is also strange, given the wartime settings of the early stories, that two such appealingly nubile girls as Worrals and Frecks, so often surrounded by servicemen, were not snapped up as wives or sexual partners.”

d by Worrals to join the WAAF” found life there rather tame after the gloss of the heroine’s flying exploits”. Interestingly she also adds, “It is also strange, given the wartime settings of the early stories, that two such appealingly nubile girls as Worrals and Frecks, so often surrounded by servicemen, were not snapped up as wives or sexual partners.”

Mary Cadogan acknowledges that W.E. Johns was writing for girls as young as twelve as well as for those on the brink of joining the armed services and thus had to be careful in depicting “romantic” man-woman relationships. However, when discussing Bill Ashton’s affectionate comradeship with Worrals, I think she underestimates just how cleverly the whole “affaire” is played out by saying merely that “when things threaten to get too passionate” that “Worrals firmly puts him down”. There is a lot more too it than that. It is time to have a look.

At the beginning of “Worrals of the WAAF” she finds herself in trouble for disobeying routine orders. She has been flying a Reliant fighter and finds herself hauled up in front of Squadron Leader McNavish. When she learns that Flying Officer Ashton, her “particular pal” as Johns first describes him, is also in trouble she tries to take the blame.

“It was not his fault, sir,” protested Worrals hotly. “I persuaded him to do it.”

McNavish is not sympathetic and Bill has his leave cancelled. Worrals confesses to Frecks that she is “sick about Bill” and the trouble she led him into. However, Bill takes it in his stride.

Presently Bill walked past smiling. “Don’t worry, kid,” he called.

“Don’t call me kid,” flared Worrals. “Then with a change of tone: “What did he do to you ?”

Bill has had his leave cancelled but he doesn’t bear any grudges. Very soon afterwards when Worrals gets a chance to shoot down an enemy she steels herself to do it and then receives a compliment from Bill.

In fact, I couldn’t have done it better myself.

When he once again calls her “kid” she turns on him.

I do wish you wouldn’t call me kid,” snapped Worrals. “How old are you, anyway twenty ?”

Worrals herself is just eighteen and Frecks a few months younger. All of them are just the right age for roma ntic attachments to be formed. It is not until the next story, “Worrals Carries On”, that further signs of what is between Bill and Worrals begin to emerge. The story opens with Worrals and Frecks counting back in the twelve planes in Bill’s squadron. Only eleven appear and then this conversation ensues,

ntic attachments to be formed. It is not until the next story, “Worrals Carries On”, that further signs of what is between Bill and Worrals begin to emerge. The story opens with Worrals and Frecks counting back in the twelve planes in Bill’s squadron. Only eleven appear and then this conversation ensues,

“I wonder who’s gone ?” Worrals’ voice was little more than a whisper.

“Don’t worry, it won’t be Bill,” returned Frecks confidently.

“I didn’t say anything about Bill,” protested Worrals. Flying Officer Bill Ashton was her particular pal among the officers of the squadron.

Frecks smiles knowingly. “I know you didn’t say anything,” she answered blandly. “But that’s what you were thinking.”

“Since when have you been clairvoyant ?” inquired Worrals sarcastically.

“One doesn’t need to be a thought reader to know who you are most concerned about,” murmured Frecks casually.

Worrals doesn’t deny it and doesn’t go through any ritual reiteration of feelings about friendship and comradeship not necessarily being the same as affection. Frecks knows that there is something extra there that Worrals appears to be suppressing. Bill himself is certain susceptible to her charms. In “Worrals of the WAAF” he broke regulations by teaching her how to fly the Reliant and in this story he is prepared whilst on guard duty, after some persuasion, to ignore the fact that Worrals has come back late from leave and has visited London which is out of bounds.

“All right I’ll do it. Your names won’t appear in my report, but if there’s a row, and it’s found out, you’ll have to ….”

“I’ll come and whisper nice things to you through the prison bars,” promised Worrals.

The crucial moment in the adventure comes when Bill has to pilot the aeroplane that is going to take the two girls over to parachute into occupied France. Worrals notices his worried expression and probes to find the truth.

“I don’t like the idea of you doing this job.” Bill’s manner was curt.

“It’s a bit late in the day to start talking like that. What’s come over you ?”

Bill turned in his seat and looked up into Worrals’ face. “Don’t you know ?”

“No how should I ?”

Bill seemed to have difficulty in speaking. “Well, it’s you,” he blurted.

“Me ?”

“Yes, you. You know, kid, you mean an awful lot to me. If anything happened to you on this show I should never forgive myself.” Bill caught Worrals’ hand and held it.

“Yes, you. You know, kid, you mean an awful lot to me. If anything happened to you on this show I should never forgive myself.” Bill caught Worrals’ hand and held it.

For a moment Worrals stared in genuine surprise. Then, recovering herself, “Bill,” she said, “you’re not by any chance making love to me, are you ?”

“Call it that if you like.”

“But, Bill ! Couldn’t you think of a better time and place to start this sort of conversation than in the cockpit of an aircraft with the entire squadron standing round ?”

“It wasn’t until I saw you with that brolly on, and realized that you might not come back…”

“Hey, wait a minute, Bill,” broke in Worrals. “D’you want me to burst into tears ? Be yourself. You’ll laugh at this nonsense in the morning.”

Mary Cadogan uses this last sentence to suggest that Worrals is putting him firmly in his place and that this kills the romance. This is far from my impression. It is also not what Frecks suggests.

“Well, for the love of Mike ! Have you two gone crazy ?”

As the machine makes its way towards France Worrals starts brooding.

The girls fell silent. Worrals was thinking about Bill’s last words, which really only confirmed what she had long suspected.

Later she returns to the pilot’s cabin and sits next to him and asks him if he feels better.

“I shall feel better when I’ve got you safe back home,” muttered Bill.

“Upon my life you’re positively depressing,” protested Worrals.

Bill threw her a glance, and a smile. “Sorry, kid don’t take any notice of me. I had to tell you though.”

“Don’t apologize, Bill I like it,” answered Worrals, and bolted back to the cabin.

Saying that she likes his declaration of love is hardly a way of putting a stop to the potential romance. Nor is giving his hand a firm and meaningful grip just before she returns to Frecks and the parachute descent.

You can see the sort of trouble that W.E. Johns was getting himself into with this sort of scene. He does the same manner of thing with poor Ginger in “Biggles ‘Fails to Return” where he and Jeannette can only fulfil their feelings by going “walking and swimming”. Certain things have to be implied rather than stated when your readership could be so young. At the same time the possibility of romance with a young “debonair” Spitfire pilot with nine victories to his credit would surely be an aspect of the books that appealed to young girls approaching the age when they could join the WAAF. At times these older teenagers must have had to do an enormous amount of "reading between the lines” whilst their younger sisters would wonder why Frecks was making a fuss as Bill escorted them back to the girls’ quarters.

Frecks, arm in arm with Suzette, walked on. Just inside the door she turned. “Worrals,” she said sternly, “what are you doing ?”

Worrals looked up. “Bill was just helping me off with my mackintosh, that’s all,” she explained.

Frecks shook a warning finger. “What you were doing is not scheduled in the night’s operations,” she remarked sarcastically.

“Nor were a lot of other things,” returned Worrals.

The echo of Bill’s laugh came out of the darkness.

And now the author is stuck. Much as his readers might have wanted romance to go along with the action Johns was creating a series character and not a one-off heroine. At this point the war was really just beginning and Worrals was needed to “do her bit” and not to retire to the sidelines. The romance could be allowed to continue but it must be kept severely in check. This more muted approach is shown in “Worrals Flies Again” where Frecks points out that Bill is not going to like the fact that she is heading off into the unknown in the flimsy-looking Midget aeroplane. She says that Worrals and Bill have been getting “pretty pally” and also that Bill has a “crush” on Worrals. By this time, however, Bill seems to have worked out just what he can expect from the relationship. When Worrals tells him that she can’t reveal any of the details of her mission there is this reaction.

Bill didn’t reply immediately. He looked at Worrals, then at the aircraft. “If I can help, just let me know.”

The only contact between them before she departs is as follows:

Bill nodded seriously. “Be careful, kid,” he said holding out his hand.

Worrals smiled as she took it. “We’ll be back,” she said evenly.

Because of what has happened in “Worrals Carries On” this is now understatement of what he feels for her. Even the word “kid” so often used in their previous banter has now taken on a new tenderness.

Later in the book W.E. Johns cleverly reverses one of the classic stereotypical scenes of romantic adventure the “damsel in distress” routine. Bill falls into the hands of the Gestapo and Worrals takes amazing risks to ensure his escape and rescue. When she first sees him under guard she is taken completely by surprise.

Worrals’ eyes switched to his face, and there stopped. Her heart seemed to stop. In fact, everything seemed to stop.

This is where the reader can choose their own interpretation of what she is feeling. Is it solely shock that makes her heart apparently stop ? Or is it the feelings she has for Bill that make the shock even harder to bear ? When she gets a few moments to think she realises that Bill would have come to France precisely because Squadron-Leader McNavish would inform Squadron-Leader Yorke, the intelligence officer in charge of the operation, that “there was an attachment between Bill and herself”. Later in her ruminations she realises “thoughts of Bill entirely filled her head”. However, it is the friendship and comradeship angle that is played up the most.

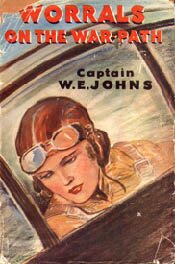

In “Worrals on the War-path” Bill’s affection for Worrals seems to be taken for granted by all concerned. He makes no bones about what he feels for her. He pretends to be jealous of the French comrades with whom she is working on the Causse Mejean. When he calls her “kid” once more and gets told off, he protests that she won’t allow him to call her “darling”. At the end of the book Johns makes him even more explicit in his emotions.

“The next time I fall in love I’ll choose a girl who stays at home and ….”

“Leads a nice, quiet, respectable life, and puts your shoes by the fire to warm, and here, please look where you’re going. If you rock the machine like that Frecks will think we’ve shed a wing or something.”

Frecks’ face appeared around the bulkhead. “Say ! What goes on ?”

“It’s all right,” answered Worrals. “It’s only Bill. He usually chooses moments like this to get emotional. Don’t take any notice of him.”

It seems that even a partial embrace has to be suggested by an unexpected movement of the aeroplane and Bill’s desire for further involvement is to be deflected by the sarcastic combination of Frecks and Worrals when they land safely back in England.

“What a nuisance men are.”

“Never mind, they have their uses,” admitted Worrals backing away from the cockpit with Bill in pursuit.

The C.O.’s voice, crisp and curt, cut in. “What’s going on in there ?”

“Flight Officers Worralson and Lovell reporting back for duty, sir,” answered Worrals weekly.

This sustained “will they, won’t they” romance lasts through the first four books. However, its purpose is much more important than its content. You see, in the parts of the books which we have not explored, Worralls has to overcome feelings that might be thought to be one of the major drawbacks of any woman in war-time, particularly one that has such a dramatic career as this particular member of the WAAF. In particular she has to kill the enemy. She has to deny any so-called feminine instincts and pull the trigger. Johns ensures that all three ingredients are in place: the resolution to go through with the unpleasant but necessary slayings, the qualms of conscience and self-questioning that surround these events, and afterwards the secure return to being a woman who is the object of a healthy and tender desire by an eminently likeable young man. For a long time Bill is kept at bay not by Worrals becoming “hard-boiled” after facing so many dangers but by the inappropriateness of romance in the war-time context. They simply can’t settle down together whilst there is work to be done.

Johns postpones the inevitable and yet maintains the whole debate about the role of women in the world of war by two contrasting adventures. “Worrals Goes East” takes the two WAAFs to Syria where women are treated with even less respect than they are in the British Armed Services. It is through the transformation of the opinion of their formidable “bodyguard, Nimrud, that W.E. Johns shows the impact that the young women can make.

Early in the story Frecks comments,

“You’re not really concerned about us, are you ?” remarked Frecks tartly. “You just don’t want your face blackened.”

Nimrud shrugged. “What is a girl, more or less ?”

His conventional view that a bint is worthless, particularly in the theatre of war, is bound to rankle with all the female readers. But they know what is to come and, by the end, Nimrud is singing quite a different tune about Frecks.

“As God is my witness, the brain of that bint must move even faster than her legs,” declared Nimrud in a voice of wonder. “Perhaps it is the cause of the spots upon her countenance,” conjectured earnestly. “W’allah ! If so, I pray my children have such spots.”

This is a very gratifying tribute to her courage and Johns has very effectively shown that the Arabs’ attitude to their womenfolk and the taboos that surround them actually allows him to use his heroines in the way he could never have used Biggles or Gimlet. There is even the implied threat that if Worrals and Frecks fail in their mission, the daughters of the American professor will be sold off to a desert sheik to suffer the conventional fate worse than death.

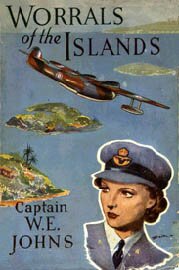

“Worrals of the Islands” takes the two girls even further away from Britain and the possibility of further inter-action with Bill. This time it is the feeling that the missing girls; nurses, wrens and WAAFs who have been stranded after the fall of Singapore will only be found if someone with a personal interest sets out to rescue them. One of the Australians they meet suggests that they can expect the worst if they fall into the hands of the Japanese.

Worrals shook her head, slowly, smiling faintly.

“Don’t worry, big boy; that won’t happen. There will always be one bullet left in my gun.”

This is what we have come to expect from our heroine. But when the war ends the awful moment can not be put off for much longer. W.E.Johns has to make decisions about his three service series heroes as the moment of demobilisation draws near. Like the rest of the country they have to face the future without a clearly defined purpose in life.

The “Biggles” bandwagon proved to be the easiest to keep on the road. His new role in the Air Police fits him like a hand into a tailor-made glove and there are places there for Algy, Ginger and Bertie as well. Gimlet and his comrades are more difficult to settle and there are several admirable sections in “Gimlet Comes Home” but especially in “Gimlet Lands a Hand” where the difficulties of settling back into civilian life nearly overwhelm Copper, Trapper and Cub. Most difficult of all, however, was Worrals, for here he had to deal with the problem of Bill.

The last time he get into this “author trap” with Ginger’s romance with Jeannette in “Biggles ‘Fails to return’” he simply ignored all that had happened and went on writing more adventures. He was helped at the time by the fact that the chronology of the “Biggles” stories during the war is not that easy to trace with pre-war adventures like "Biggles in the Jungle” cropping up amongst the flow of fighting the Germans and the Japanese in various different parts of the world.

In “Worrals in the Wilds” both W.E. Johns and Worrals make their decisions and admittedly the door to love and settling down is never quite closed but scarcely kept ajar. Once the war is over there seems little to prevent Bill and Worrals sharing a life together. Indeed Frecks believes this is what is likely to happen when Bill calls round to see them in their Knightsbridge flat.

Frecks was not surprised to see Bill. In fact, she had been expecting him, and when she opened the door to him she thought she knew what he had come to fetch. When he went he would take Worrals with him. That was what Frecks thought.

One rather wishes that Frecks had cleared out of the way at this point but she is present when Bill discusses his future with them.

Pressed for an explanation Bill asserted looking hard at Worrals that he had given the project of matrimony some earnest consideration, but had decided this would be neither fair to himself or the girl while the world was in its present state of chaos. It would be better, he opined, to wait until the clouds rolled away, leaving a somewhat clearer course.

This has made it too easy for Worrals. Her agreement with this course of action allows her to evade the commitment that he so clearly wants. As Frecks observed:

With this decision Worrals agreed so readily that Bill’s face fell, giving Frecks the impression that this was only a feeler to test Worrals’ reactions to the marriage question. It would, she thought, take little persuasion to cause him to change his mind.

After he outlines his scheme for setting up the air transport arrangements for his uncle in South Africa he renews his proposal,

Would Worrals like to come along as Mrs. Bill Ashton, of course ?

Her response is both to refuse and to equivocate.

Worrals said quite definitely that she would not. The war was only just over, and she wanted to get her breath before rushing half-way round the world, with or without a husband. Apart from that, the presence of a woman in such a place as Bill had described would be a constant embarrassment, and perhaps responsibility, to the male members of the party. She was very fond of Bill, and all that, but she wasn’t quite crazy and after all, they still had the best part of their lives in front of them.

Parts of this speech seem extremely hollow when you consider the extreme conditions that she has put up with and her resolution to do anything that a man can. As for "half-way round the world”, the events in “Worrals of the Islands” and “Worrals Goes East” make this strand of her argument seem very thin indeed. In some ways, though there are many well-constructed and interesting adventures to follow, W.E. Johns has yielded to the demands of his publishers and, presumably, his readers. He has decided that the relationship must be allowed to fizzle out but not before Worrals rescues Bill from the claws of death once more. Interestingly, having refused him and watched him go off to Africa by himself, Worrals finds herself very soon brooding over his fate.

“I’m thinking of flying out and having a look round,” returned Worrals, with studied nonchalance.

“If you’re in love with him why didn’t you go out with him ?” asked Frecks bluntly, exercising the candid privilege of long friendship.

“Who said anything about being in love ?” flared Worrals. “Bill was a good pal to us when we were in the Service. We owe him something for that.”

The issue of the extent of her affection for Bill is kept alive with perhaps a suggestion that Worrals doesn’t yet know her own mind or feel able to yield to her feelings. Frecks doesn’t reject the idea of love being behind her concern, referring to Bill as Worrals’ “roaming Romeo”. The end of the book is a let-down. Bill can think of a much better arrangement that Worrals flying tamely back to Britain.

“Ah-huh,” sighed Frecks. “Here we go again.”

Worrals soon set her fears at rest.

“You’ve got plenty to do without getting involved in house-keeping complications,” she told Bill. “One thing at a time is an old, but sound policy. Besides, as traffic manager you’ll have to live at Magube, and, frankly, I’ve seen enough of that sun-smitten wilderness to last me a life-time. When I settle down it will be where the grass grows green….”

She (and Frecks) will come back when he’s got things going. First it was the war and now it is work that is used as a means of postponing fulfilment. So both Bill and the readers are left with something that lies between a hope and a vague promise. And Bill never appears again even when the sequence of eleven books comes to an end. All other thoughts and opinions about love and relationships are now considered at second hand and they provide us with very few clues about Worrals’ ultimate destiny.

“Worrals Goes Afoot” takes us back to the world of the Middle East and the low esteem with which women are held in that area of the world. Once again Worrals and Frecks overturn conventional wisdom and a certain frisson is obtained from the fact that this time they are the ones that are likely to end up as slaves in a harem. “Worrals in the Wastelands” explores the inhumanity of the beast of Belsen as our heroine and Frecks bring to justice Anna Schultz, the merciless wardress of a Nazi concentration camp. The fact that Schultz has used her charms to coerce other German officers into doing her will provides an interesting counter-point to her grotesque cruelty as outlined in the first pages of the book. Most surprising of all is the colony of women set up by Celia Haddington in “Worrals Investigates”. A more vivid example of the failure of women without men it would be difficult to imagine. Worrals and Frecks expose not only a state of semi-slavery but also many examples of sheer folly and fecklessness that seem to demonstrate that men and women are destined to work together if things are to go well.

In his foreword to “The First Biggles Omnibus” W.E. Johns declared that “Gimlet and Worrals are on leave.” Worrals never did return to active duty after 1950. At the most she would be 28 still not too late to claim Bill and settle down.

Let us, however, return to where we began with the characters in the opening picture. The third person featured is Janet, winner of the George Cross, and a girl of some spirit. The last page of “Worrals Down Under” finds her both rich and happy. Her opal bearing property in the middle of nowhere is snapped up by an “important syndicate” and her private life is similarly settled.

The matter was finally clinched, as far as Janet was concerned, when Dan Terry asked her to marry him. This offer she also accepted, for she had got to know the cheery police officer very well while the investigations were proceeding.

We are told that “Worrals and Frecks stayed on for the wedding” and that later they went home to the United Kingdom, “richer in pocket and in experience.” Perhaps Janet’s fate should have given Worrals some hints after all Johns was showing that he was not averse to a conventional “happy ending”. Unfortunately, however, the matrimonial fate of Worrals, the ultimate flying heroine, will always remain, “up in the air”.