Cover | Archive | Crime | Fantasy/SF | Popular | Historical | Comics | Non-Fiction | Children's |

Table of Contents Open for debate

Reviews

Feature Articles

Introducing the Original Dangerous Books for Boys

Introducing the Original Dangerous Books for Boys

Nostalgia: Things are what they used to be!

Nostalgia: Things are what they used to be!

Nostalgia Central: Carlton Books

Nostalgia Central: Carlton Books

Elizabeth Chayne's Reading Room

Elizabeth Chayne's Reading Room

Personalised Noddy Books from Harper Collins

Personalised Noddy Books from Harper Collins

Stories and Serials

Phyllis Owen: A Soft White Cloud Chapter Four

Phyllis Owen: A Soft White Cloud Chapter Four

Paul Norman: Heraklion ~ Outcast

Paul Norman: Heraklion ~ Outcast

What makes a book a classic?

By Paul Norman

What constitutes "classic" literature? Wikipedia gives one possible definition: "many view any pre-1900 book still in print as a classic, and many books are classed as modern classics because of their contemporary significance or perceived future significance." You can choose to agree, or to disagree. For me, stating pre-1900 as the watershed for what becomes a classic rules out a whole load of "classics" written in the first years of the 20th century, for instance, such titles as:

What constitutes "classic" literature? Wikipedia gives one possible definition: "many view any pre-1900 book still in print as a classic, and many books are classed as modern classics because of their contemporary significance or perceived future significance." You can choose to agree, or to disagree. For me, stating pre-1900 as the watershed for what becomes a classic rules out a whole load of "classics" written in the first years of the 20th century, for instance, such titles as:

John Buchan: The Thirty-Nine Steps

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: The Lost World

Rudyard Kipling: The Just-So Stories

Edgar Rice Burroughs: Tarzan of the Apes

Pre-1900 also suggests that an author who wrote books before 1900 wrote classics, but anything he or she wrote that was published after 1900 was not a classic because of the cut-off date. Wikipedia also offers the suggestion that a classic is a book marking a turning point in history. Where does that leave Wuthering Heights, Middlemarch, Huckleberry Finn and the like? These are simply great stories. For me, a better definition of "classic" would be a book that has passed into publishing history as being of some significance. In that sense, there are thousands of books published during the last century that qualify, and hundreds of thousands that do not. I've not read Mein Kampf – it simply doesn't appeal to me. But I would personally think that it should be classed as a classic.

Pre-1900 also suggests that an author who wrote books before 1900 wrote classics, but anything he or she wrote that was published after 1900 was not a classic because of the cut-off date. Wikipedia also offers the suggestion that a classic is a book marking a turning point in history. Where does that leave Wuthering Heights, Middlemarch, Huckleberry Finn and the like? These are simply great stories. For me, a better definition of "classic" would be a book that has passed into publishing history as being of some significance. In that sense, there are thousands of books published during the last century that qualify, and hundreds of thousands that do not. I've not read Mein Kampf – it simply doesn't appeal to me. But I would personally think that it should be classed as a classic.

Finally from Wikipedia, "a certain thing of a classic is that a classic is very highly revered in the authors' region or ethnic (sic) and is well-classified as a "must-read". Well, at least once a year I recommend a title as being a "must-read", but I would hesitate to say that each of these chosen books of mine are classics. Another definition could be the style of writing. If a writer emulates the style and the language of, say, Dickens, or R L Stevenson, can they be said to have written a classic, do you think? Some of the language used by Stephen King is "classic" in this sense, particularly towards the end of the Dark Tower series.

By the time I was ten years old and revising for the 11+ examination in June 1957, I was well-read in the "classics". Relatives had bought for me various Dickens titles, some abridged, but still substantial, The Three Musketeers, Lorna Doone, Wuthering Heights and quite a few others. King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, together with The Adventures of Robin Hood, became my favourite books, the ones I would sit and read in bed on a long summer's evening. I knew little about Shakespeare, though I'd heard of him and of his enormous contribution to literature, of course, and amazingly, I didn't come to Jane Eyre until my thirties, when it was a set book for my Open University Arts Foundation Course. The Prisoner of Zenda came my way in the fourth and last COMMANDER BOOK FOR BOYS. Various other classics found their way onto my bookshelves after I'd watched the movies.

When I found myself in the company of a quite different peer group, I thought myself adequately grounded in the classics – I certainly knew, or thought I knew, what a classic was. In my second year at Grammar school, I ran into trouble. By then I'd graduated to Dennis Wheatley, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Mazo de la Roche and Lesley Charteris. At every opportunity I would ask my English Literature teacher why those authors, who then sold by the bucketload, were not considered classics. Now, of course, some of them are. You could even argue that some earlier Stephen King titles, like THE STAND, THE SHINING, IT and CARRIE are classics – modern classics, that is. For me, onee measure of a classic is not just how well it's written, nor what its subject matter is, but how there is still demand for it.

I wouldn't class HARRY POTTER as a classic, but I would certainly class TARZAN OF THE APES and THE DEVIL RIDES OUT as modern classics. The WHITEOAKS saga are without doubt the best of their genre, and rival any of the Thomas Hardy novels or Anthony Trollope and John Galsworthy in relation to family sagas. The FORSYTE SAGA is no better than WHITEOAKS, certainly, and in many ways, not least the strength of the characters, a darned site worse.

Nowadays, there is a genre known in publishing circles as "literary fiction". What is fiction if it is not literary? I don't have a lot of time for literary fiction – it's aimed purely at intellectuals, and smacks of the Emperor's New Clothes as far as I'm concerned. It seeks to pretend it's something rather special, something the ordinary man or woman in the street would not be able to read because it's beyond them. It fuels the "them and us" attitude of reviewers in the broadsheets.

Give me a Bernard Cornwell or a Philippa Gregory any day. And today, you can give me a James Delingpole, because for me, he's the man of the moment. COWARD ON THE BEACH was last month's book of the month, a must-read, an example of all that's good in modern story-telling. But will it be considered a classic in years to come? It may be that the author didn't set out with the vision that his superb creation would some day be regarded as a classic.

Popular fiction is at its best right now, particularly in the area of historical novels. Philippa Gregory steers us through the Tudors and Stuarts with consummate ease, matched by Bernard Cornwell's Crimea and now Dark Ages chronicles. I learned more Napoleonic and WWII history from reading Dennis Wheatley's Roger Brook and Gregory Sallust stories than I did from text books, and provided you trust the provenance of the author, I can see no problem with that. Now I know that Wheatley was an arch-Tory, I have reconsidered some of the history he taught me; factual but biased in some ways. That's fine as long as you're aware of it. THE DEVIL RIDES OUT has found its way into literary lore as a modern classic not because it's a rattling good story, but because it is a superb example of faultless horror storytelling, just as DRACULA is. THE HAUNTING OF TOBY JUGG is equally flawless, and a modern horror classic. Three of Wheatley's classic horror novels have been reprinted this year by Wordsworth Editions: THE DEVIL RIDES OUT, TO THE DEVIL: A DAUGHTER and THE HAUNTING OF TOBY JUGG. Now these three are classics, but just because the publishers decide to give a retro author another outing doesn't mean it's a classic, though they do tend to dress them up as such.

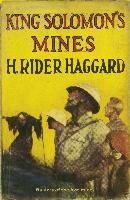

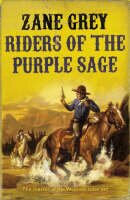

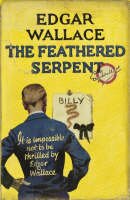

There are various publishing houses who regularly turn out new editions of "the classics". This month Macmillan publish a beautiful slipcased edition of ALICE'S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND and THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS. The same title can be had as one of the comparatively recent VINTAGE CLASSICS. Penguin "cheap" classics, which started life as £1 titles and now come out at £2, publish GRIMMS' FAIRYTALES, though it's not complete. Vintage also publish the same title, but theirs is complete. Penguin Books, seizing on the initiative of THE DANGEROUS BOOK FOR BOYS, recently launched a series of Boys' Own adventures, including John Buchan's THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS, THE RIDDLE OF THE SANDS and SHE, amongst others. Hodder were already seeing an opening for retro publishing with their first five Yellow Jackets, which are: BULLDOG DRUMMOND, KING SOLOMON'S MINES, GREENMANTLE, Edgar Wallace's THE FEATHERED SERPENT, and Zane Grey's RIDERS OF THE PURPLE SAGE.

There are various publishing houses who regularly turn out new editions of "the classics". This month Macmillan publish a beautiful slipcased edition of ALICE'S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND and THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS. The same title can be had as one of the comparatively recent VINTAGE CLASSICS. Penguin "cheap" classics, which started life as £1 titles and now come out at £2, publish GRIMMS' FAIRYTALES, though it's not complete. Vintage also publish the same title, but theirs is complete. Penguin Books, seizing on the initiative of THE DANGEROUS BOOK FOR BOYS, recently launched a series of Boys' Own adventures, including John Buchan's THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS, THE RIDDLE OF THE SANDS and SHE, amongst others. Hodder were already seeing an opening for retro publishing with their first five Yellow Jackets, which are: BULLDOG DRUMMOND, KING SOLOMON'S MINES, GREENMANTLE, Edgar Wallace's THE FEATHERED SERPENT, and Zane Grey's RIDERS OF THE PURPLE SAGE.

What makes the Hodder titles quite special is their uniformity and the fact that, where possible, they used the original dustjacket. In contrast, the Penguin Boys' Own and the Vintage Classics look like, and are, simply, modern printings of classic titles – if you're going to do the retro thing, you could at least do it properly, as Hodder have done. Alex Bonham, Hodder's editor on the Yellow Jackets series, says: "The commercial series of yellow jackets were, like the old Penguin paperbacks, a striking guarantee of a damned good read when they hit bookshops back in the early 20th Century. The books themselves are rollicking escapist adventures that appeal unashamedly to boys of all ages. They are of their age indubitably and should be read with that in mind - there are some things that just would not be said these days - however if some of the old fashioned attitudes are treated with a pinch of salt then the stories are great fun to read and reveal much of a bygone age."

What makes the Hodder titles quite special is their uniformity and the fact that, where possible, they used the original dustjacket. In contrast, the Penguin Boys' Own and the Vintage Classics look like, and are, simply, modern printings of classic titles – if you're going to do the retro thing, you could at least do it properly, as Hodder have done. Alex Bonham, Hodder's editor on the Yellow Jackets series, says: "The commercial series of yellow jackets were, like the old Penguin paperbacks, a striking guarantee of a damned good read when they hit bookshops back in the early 20th Century. The books themselves are rollicking escapist adventures that appeal unashamedly to boys of all ages. They are of their age indubitably and should be read with that in mind - there are some things that just would not be said these days - however if some of the old fashioned attitudes are treated with a pinch of salt then the stories are great fun to read and reveal much of a bygone age."

So, what makes a classic? In all my time of arguing with the English Lit. teacher way back in 1958, I never once suggested that The 39 Steps was a classic – it was, even then, regarded as a modern adventure story. Same goes for H Rider Haggard's three best-known works, SHE, ALLAN QUATERMAIN and KING SOLOMON'S MINES – simply modern adventure stories for boys. Surely they weren't classics? But now they're all published by Penguin Classics, surely the arbiter of what makes a classic?

Classics – the real classics – are Jane Austen, Anne Bronte, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Tennyson, Shakespeare, Defoe, Stevenson; not just those, of course, but many more besides. But I'd like to ask a question: what sets TREASURE ISLAND apart from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's THE LOST CONTINENT and elevates it to "classical" status? For that matter, what is the difference between Doyle's THE LOST CONTINENT and Burroughs' THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT? They're both high adventure with dinosaurs, heroes and heroines. I know it could be hazardous calling something a classic simply because of how popular it's been down through the years. You open the door to all sorts of dodgy "literature" if you do that. But how else can you decide what is to become a classic?

Aldous Huxley, H G Wells, Doyle, and even authors like Frank Richards and Enid Blyton are all still as popular as they ever were – but who will decide if their work could be classified as classic? Is there a panel sitting in judgment somewhere, like the team who compile and verify the Oxford English Dictionary? I like to think that authors such as Edgar Rice Burroughs – the pioneer of pulp fiction, Dennis Wheatley – the Prince of Thriller Writers, Enid Blyton – the most popular of children's writers, and all those others I devoured so voraciously during my formative years, can now be regarded as classic writers. If they're not, why do people continue to turn back the clock. Why do the publishers continue to publish their work? For me, the outstanding "classics" this year have to be the Hodder titles. I'm grateful for the opportunity to read the complete Brothers Grimm from Vintage, but they haven't exactly gone overboard with the cover, and I'm infinitely more grateful for a reprint of Bulldog Drummond with the original dustjacket.

Aldous Huxley, H G Wells, Doyle, and even authors like Frank Richards and Enid Blyton are all still as popular as they ever were – but who will decide if their work could be classified as classic? Is there a panel sitting in judgment somewhere, like the team who compile and verify the Oxford English Dictionary? I like to think that authors such as Edgar Rice Burroughs – the pioneer of pulp fiction, Dennis Wheatley – the Prince of Thriller Writers, Enid Blyton – the most popular of children's writers, and all those others I devoured so voraciously during my formative years, can now be regarded as classic writers. If they're not, why do people continue to turn back the clock. Why do the publishers continue to publish their work? For me, the outstanding "classics" this year have to be the Hodder titles. I'm grateful for the opportunity to read the complete Brothers Grimm from Vintage, but they haven't exactly gone overboard with the cover, and I'm infinitely more grateful for a reprint of Bulldog Drummond with the original dustjacket.

For Hodder to recapture the feel and the look of the time when it was first printed took courage and vision. I used to have relatives that had BULLDOG DRUMMOND with that striking yellow front cover on theirbookshelves. It was a moment of sheer joy to pick it up and leaf through it. An added bonus to the current Yellow Jacket reprints is the inclusion of typical 1920s advertisements that match the spirit of the books, and, I'm fairly certain, such books would have carried such advertisements.

For Hodder to recapture the feel and the look of the time when it was first printed took courage and vision. I used to have relatives that had BULLDOG DRUMMOND with that striking yellow front cover on theirbookshelves. It was a moment of sheer joy to pick it up and leaf through it. An added bonus to the current Yellow Jacket reprints is the inclusion of typical 1920s advertisements that match the spirit of the books, and, I'm fairly certain, such books would have carried such advertisements.

As a publishing venture, let's hope it pays off. This is a series that cries out for success. Alex Bonham tells me there are ongoing negotiations to publish more titles in the future. Other publishers take note. The Vintage Classics Oliver Twist has a picture of a dog, presumably meant to be Bullseye. I'd rather have a Dickens with a Dickens illustration from Victorian England, myself. Same goes for the Penguin Boys' Own series. The titles are great, and the covers are eye-catching to people with an inherent interest in books and publishing. But the current vogue for nostalgia is crying out for just a little bit more in covers and binding, I feel. As for Macmillan's Alice in Wonderland – that's just perfect, faultless, timeless – a true classic. True, the Vintage version does have Tenniel's illustrations and is, therefore, a handsome volume when you open it up. From the outside, it's fairly nondescript, and apt to get lost in the crowd. I saw it on the same bookshelf where I saw the cheap Penguin Classics and the Hodder Yellowjackets. I recognised it because Vintage had sent it to me. But while the Penguins looked like classics because of their uniform livery, and the Yellowjackets were striking and inviting, the Vintage classics didn't invite me to pick them up.

I think the 1950s saw a watershed in publishing – design went downhill from then on, and the last forty-odd years have seen some real turkeys in terms of dustjacket and paperback cover designs. Nowadays, the fantasy and the history novels get the great artists, as some of them cross over genres into the realms of fantasy. The rest rely heavily on stock photography, or else, in the case of these modern "classics", minimalism. Whoever thought of publishing the Hodder yellow-jackets deserves a real accolade. It might have been inspired, as so many recent publishing ventures have, by THE DANGEROUS BOOK FOR BOYS, but that's surely not a bad thing? There's a website where you can see the various incarnations of the Dennis Wheatley books. With few exceptions, the earliest Arrow editions from the 1950s are superlative, the rest are just also-rans. The 1950s also saw the glorious Pan paperbacks, which pioneered extraordinarily good cover art, including the Whiteoak series, the war stories by Paul Brickhill, the Saint books, the Whiteoaks books, the Angelique books and the Inspector West series amongst others. This was an era of elegance and good art; of style and manners, all of which were reflected in the book covers. They weren't all classics then, of course, but many of them are now. It's not when something was published that makes a classic. It's how it feels in your hands when you pick it up to read it, the way it's written. If you treasure it, it's a classic. Of how many of today's books can that truly be said to be the case? In fifty years time, Cornwell and Gregory will almost certainly be classics, though no longer modern. Not because of the way they appear, good as that is; it's because of the class of writing that elevates these particular authors above their contemporaries. It's open for debate, of course, and what I've said above is purely my own opinion.

If you have a particular fondness for a book you think ought to be classified as a classic, why not write to me about it, let's get a discussion going about how we elevate some titles to the genre of classics. It would make a good talking point, wouldn't it? Now back to Bulldog Drummond…

Gateway is published by Paul Edmund Norman on the first day of each month. Hosting is by Flying Porcupine at www.flyingporcupine.com - and web design by Gateway. Submitting to Gateway: Basically, all you need do is e-mail it along and I'll consider it - it can be any length, if it's very long I'll serialise it, if it's medium-length I'll put it in as a novella, if it's a short story or a feature article it will go in as it comes. Payment is zero, I'm afraid, as I don't make any money from Gateway, I do it all for fun! For Advertising rates in Gateway please contact me at Should you be kind enough to want to send me books to review, please contact me by e-mail and I will gladly forward you my home address. Meanwhile, here's how to contact me:

Web hosting and domain names from Vision Internet